Doing Laps

The day that I arrived on 9 Southwest, I knew that I wasn't going to be leaving that hospital ward for a long time, or maybe ever.

This was May of 1999 in Seattle. At that time, 9 Southwest was a bone marrow transplant ward, and I was their latest and probably their youngest adult patient. I had just completed four days of intense outpatient chemotherapy with two more days to go. Enough chemotherapy to completely wipe out my immune system. Even a simple cold was going to be able to kill me, which is why I was entering the protective custody of hospital isolation.

For the immediate future, my entire world was going to be 9 Southwest, a roughly triangular shaped hospital ward with 20 rooms along the outside of the hallway and the nurses' stations, offices, and supply rooms on the inside. But the doctors reminded me on that first day that I wasn't going to be in an isolation room. I was on an entire isolation ward. I was free to walk the hallways any time I wanted to. In fact, they encouraged me to do so. They knew that every bit of exercise that I could get would help me to survive.

So I did.

I did laps. I think my second day on 9 Southwest, I did 50 laps. I even had a spreadsheet to keep track of them. I liked plowing through the mob of doctors and residents and nurses that moved up and down the hallways during rounds and, ya know, just making them scatter. I used to call it bowling for doctors.

Fast forward a few days after the chemo was done, but before the worst of the side effects had hit me. At something like 5:45 that morning, I gave up on trying to pretend to sleep through the beeping of the infusion pumps, the slowly worsening nausea, and most of all, the fear. So I rang the nurse to unhook me from my IVs and got ready to go for a walk and put on some good walking shoes, sweatpants, and a button-down shirt. I headed out of my room to discover that no one else was stirring it that out. It was basically just me and a few nurses behind the desk. The hallways were empty.

But okay, I turned right and started power walking. Went all the way down the hall, made the first left, kept going. As I approached the second corner though, a figure turned the corner and started walking towards me. As he got closer, I recognized him. It was Steve. Now, Steve was one of the other patients on the ward. Steve was in his 40s and about a week or so ahead of me on the timeline for his transplant. So I was paying a lot of attention to what happened to Steve because whatever happened to him was plausibly going to happen to me. And that morning, to put it simply, Steve looked like hell.

He was wearing old style button-down pajamas, slippers, and a plaid bathrobe. Multiple tubes led from his chest back to the rolling IV pole that was trailing behind him. In his hands, he was clutching close to his chest, one of those dark red kidney-shaped plastic bowls that are just everywhere in hospitals. More scary to me, however, was his body language. Steve was not power walking the way I was. He was hunched over, shuffling slowly, hesitantly. Each step, clearly an effort.

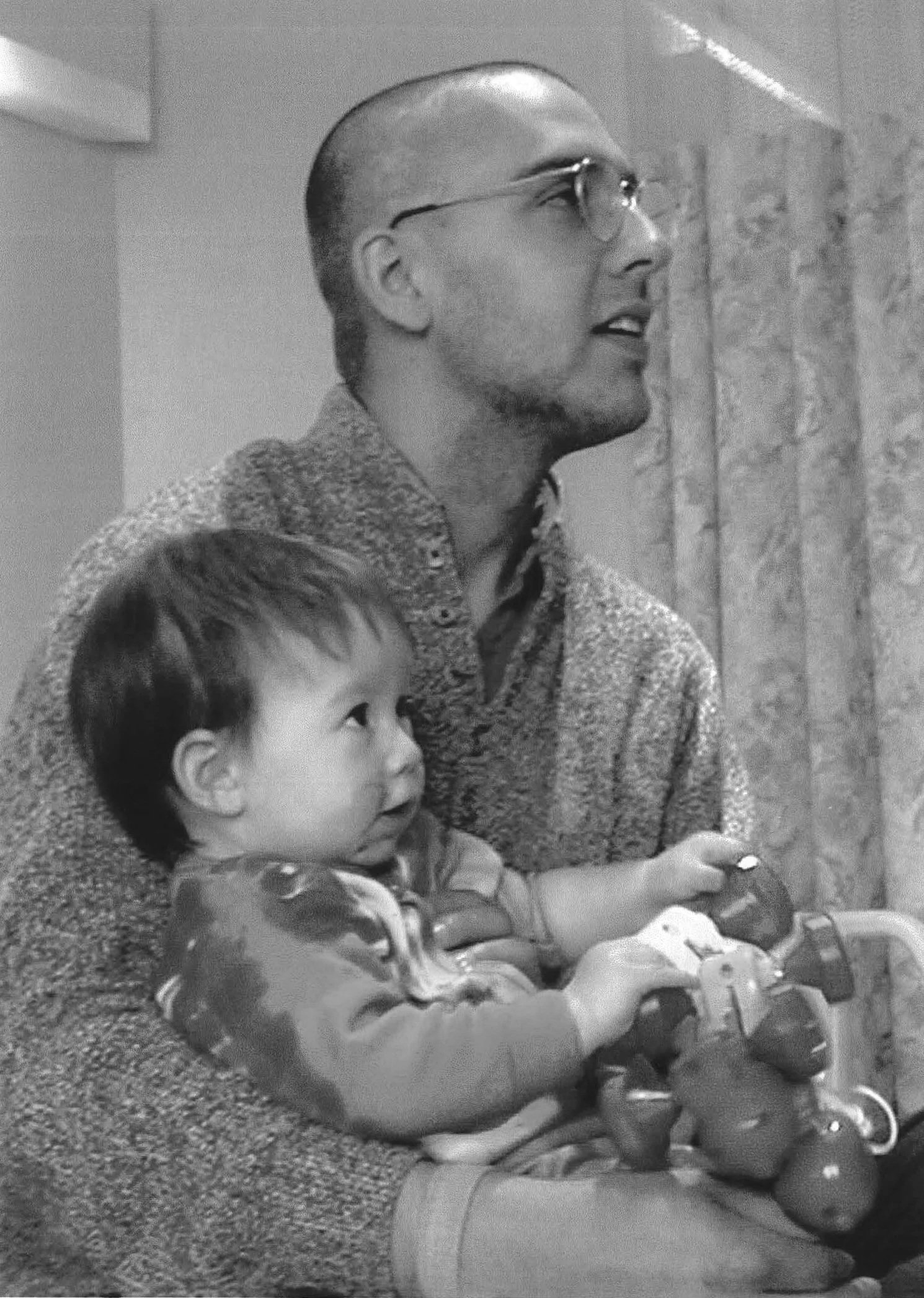

Brian and his daughter Eve in the bone marrow transplant ward

Steve and I, we locked eyes for just a moment as we passed in the hallway. We didn't say anything to each other, but I'm confident we both knew exactly what was happening in that moment. Just as I was out to do laps, Steve was out to do laps. I was wondering what my body was still capable of, and so was Steve. I was gonna try for, I think, 40 laps that morning. Steve was probably just hoping to finish one. And at 6 a.m. that morning, what Steve and I shared in that moment was a commitment to try despite our fears.

So I did.

I kept going. I didn't see Steve again that day after that first lap, but I did all 40 of my laps over the next hour, going around that triangle over and over and over. And then I went back to my hospital room, sat down on the bed, and went back to just trying to survive.

I left 9 Southwest after 30 days of inpatient care. I'll spare the details, but the fact that I'm here today talking means that roughly you know how it all turned out in the end. But that wasn't true for everyone. On that 20-bed ward of 9 Southwest, I knew of four patients who never left. Steve and I were both some of the lucky ones.

Nevertheless, my experiences on 9 Southwest changed me. They changed how I look at the world, how I look at other people, how I think about different kinds of moments. For example, to this day, if you say the word “courage” to me, the image that immediately snaps to mind is not of a firefighter charging into a fire or a soldier or those kinds of images. No, my image is a bald guy in his 40s in a plaid bathrobe slowly taking step after step after step all while desperately clutching a barf bowl.